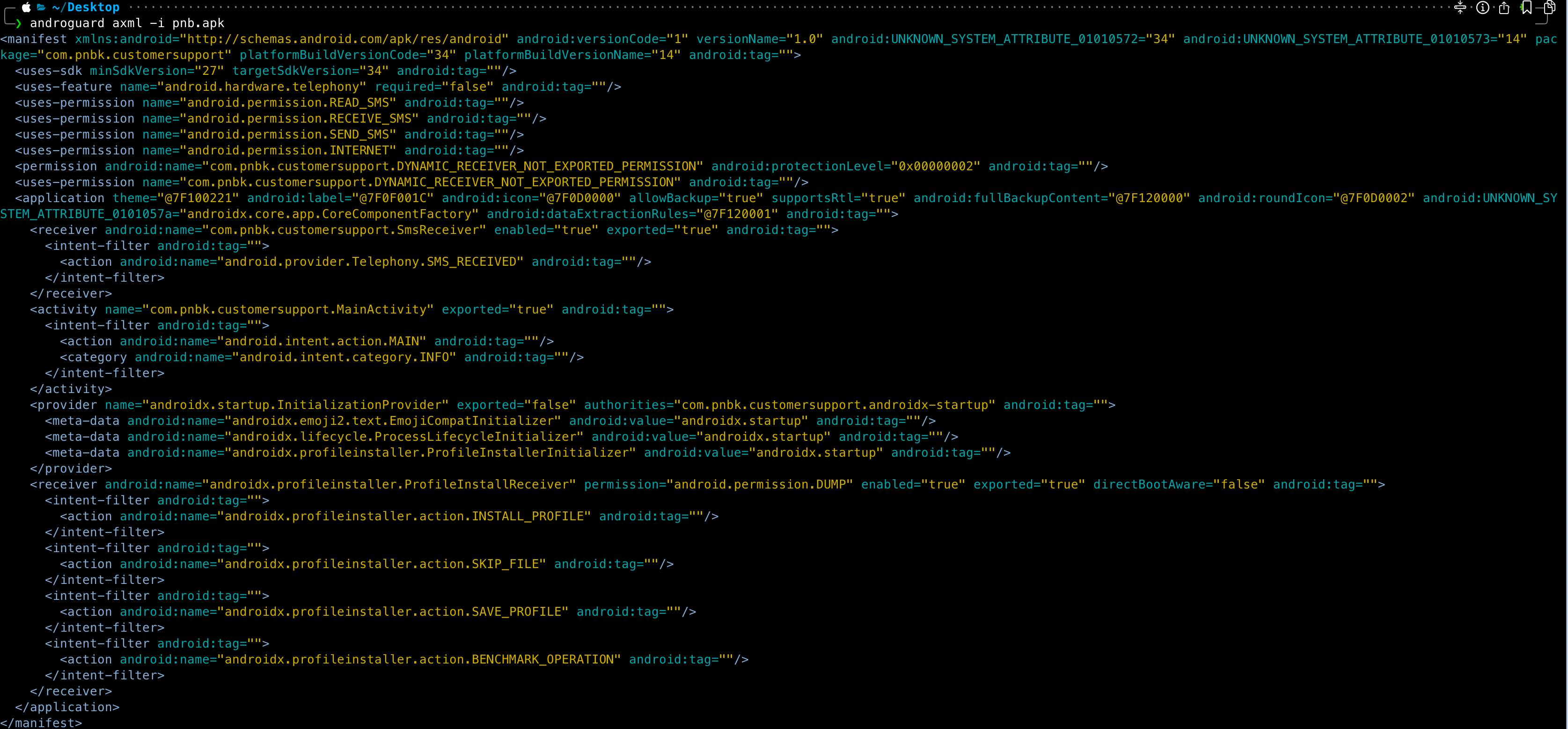

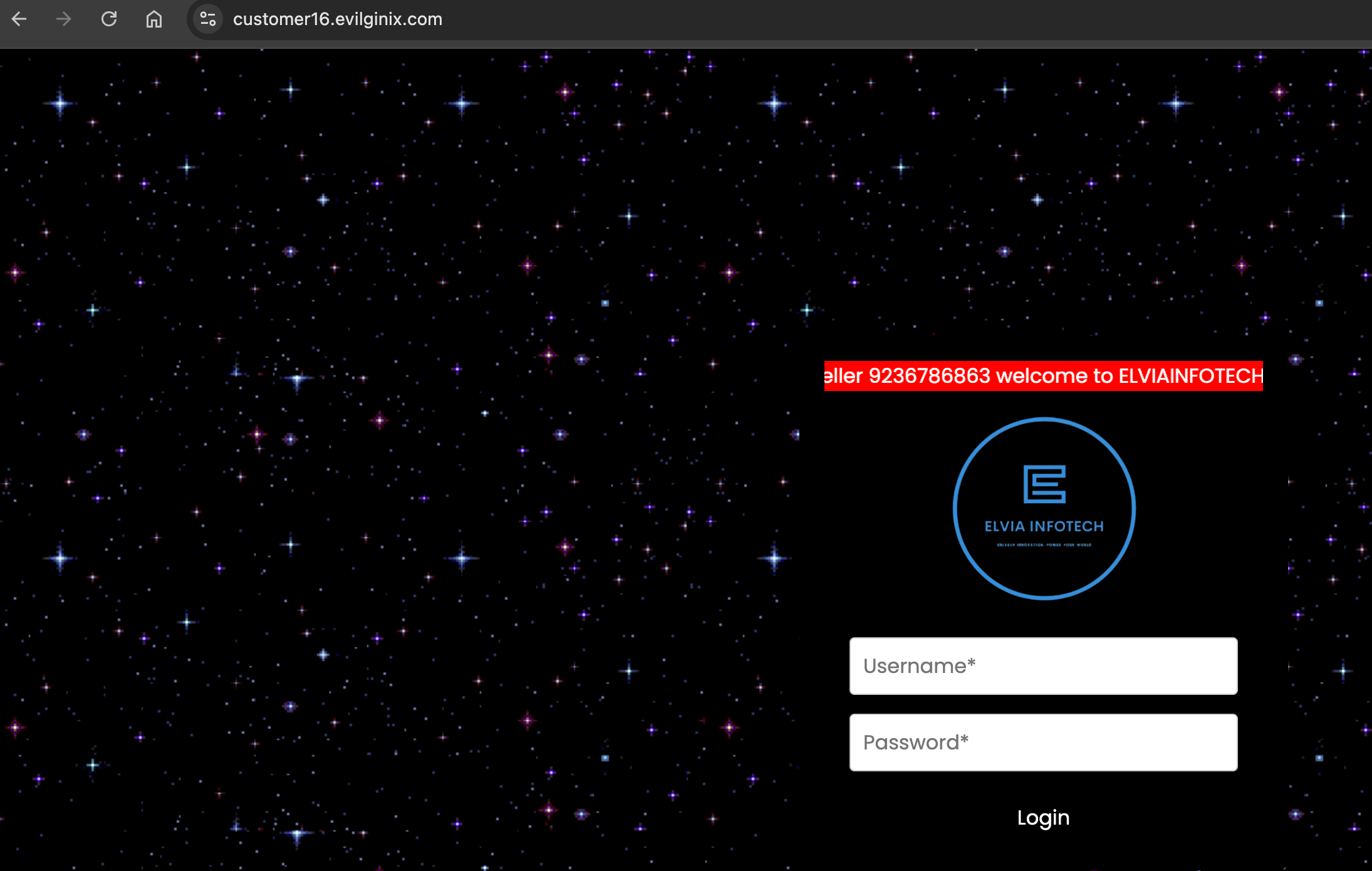

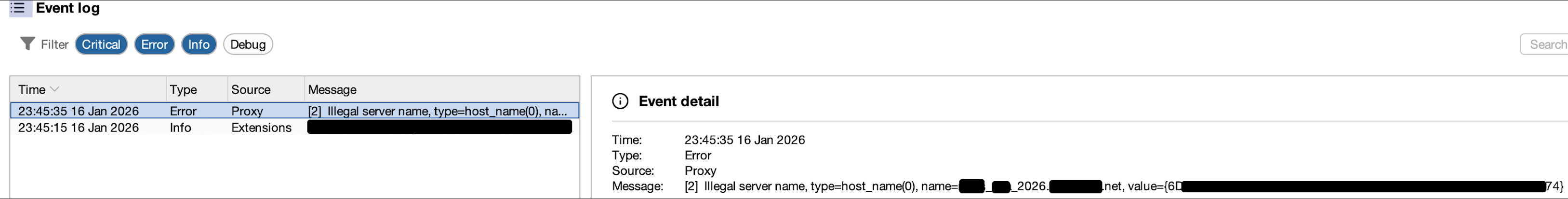

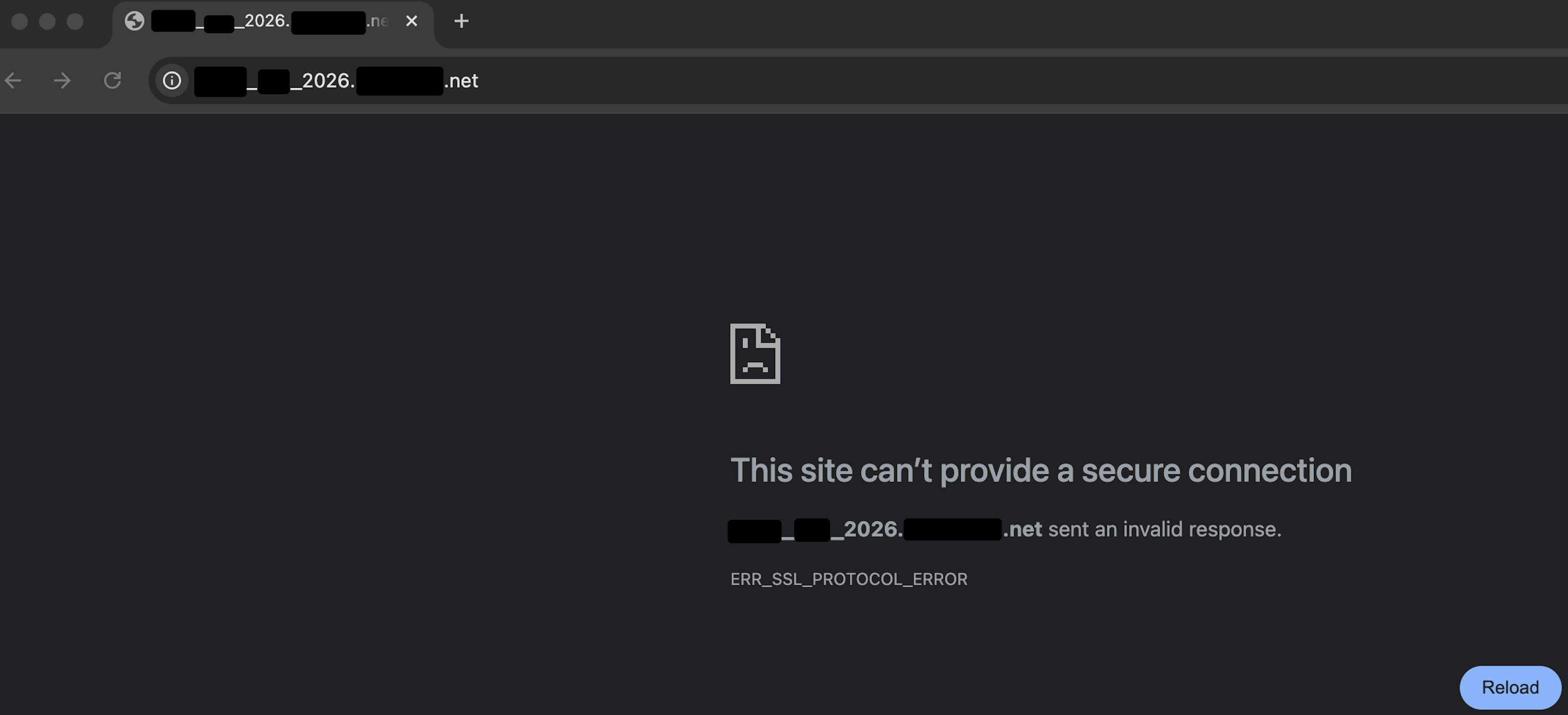

During a recent web application penetration test, I encountered an unusual issue when proxying traffic through Burp Suite. Every time I attempted to access the target application via Burp, the request failed with the following error:

“Illegal server name, type=host_name(0), name=SNIP, value={SNIP}”

The figure below shows the exact error message returned by Burp Suite.

Note: The actual domain name has been redacted due to NDA restrictions. However, a similar example domain will be used throughout this post to clearly explain the issue and solution.

How the Issue Appeared

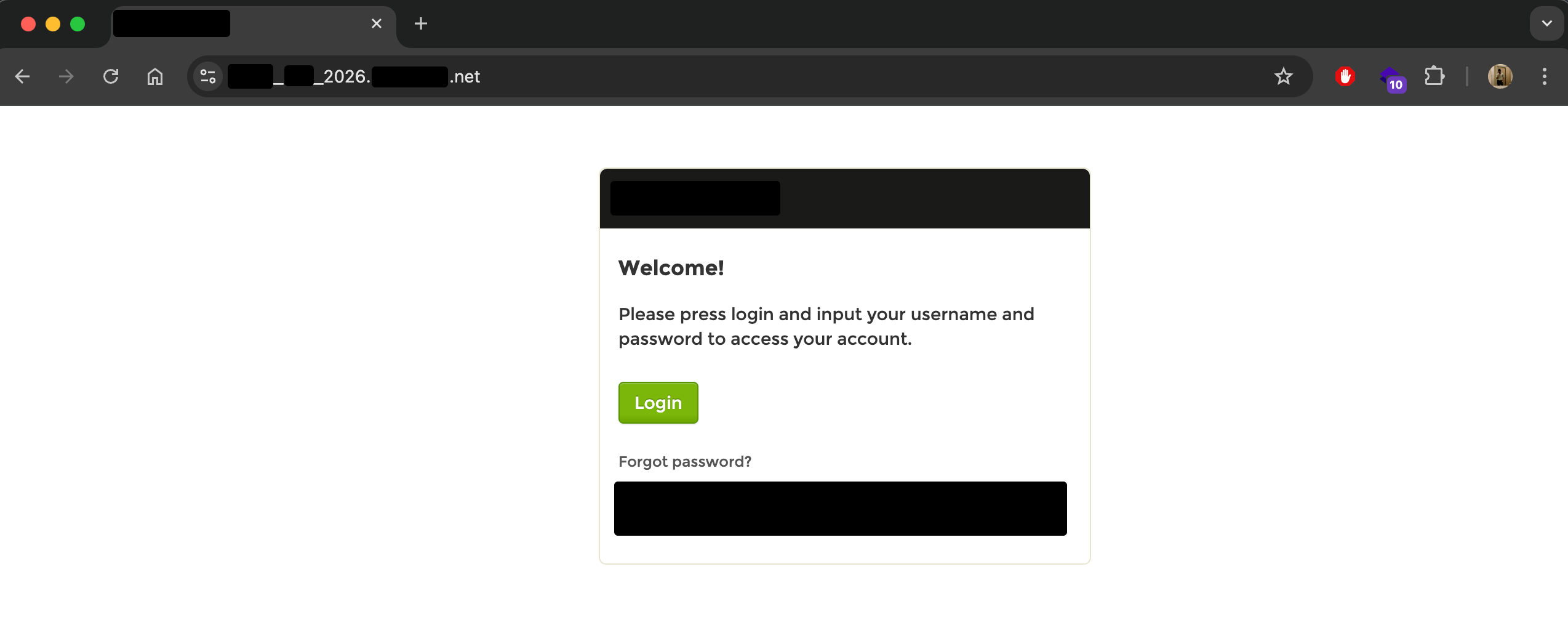

When accessing the application through a browser configured to use Burp Suite as a proxy, the page failed to load. Instead, the browser displayed an error indicating that the connection could not be established.

The figure below shows the error displayed in the web browser when traffic was proxied through Burp Suite.

Interestingly, when the same application was accessed without Burp Suite (direct connection), it loaded perfectly fine. This confirmed that the issue was not with the application itself, but specifically with how Burp Suite was handling the hostname.

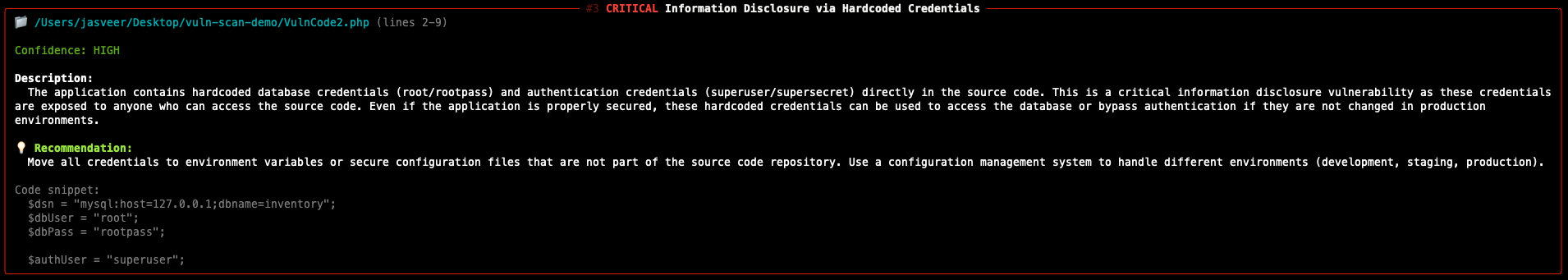

Root Cause Analysis

After some investigation, I discovered that the problem was caused by the use of underscores in the domain name.

According to DNS standards, underscores are not valid characters in hostnames. While many browsers and applications still tolerate them, Burp Suite enforces stricter validation and rejects such domain names.

For example, consider the following domain:

2026_Test_jasveermaan.com

This domain contains underscores, which Burp Suite treats as invalid, resulting in the “Illegal server name” error.

To continue testing the application through Burp Suite, a workaround was required that would allow Burp to process the domain correctly without modifying the target infrastructure.

Workaround Solution

The solution involves two main steps:

- Creating a custom DNS override in Burp Suite

- Using Match and Replace to rewrite the hostname in HTTP requests

Let’s go through the steps in detail.

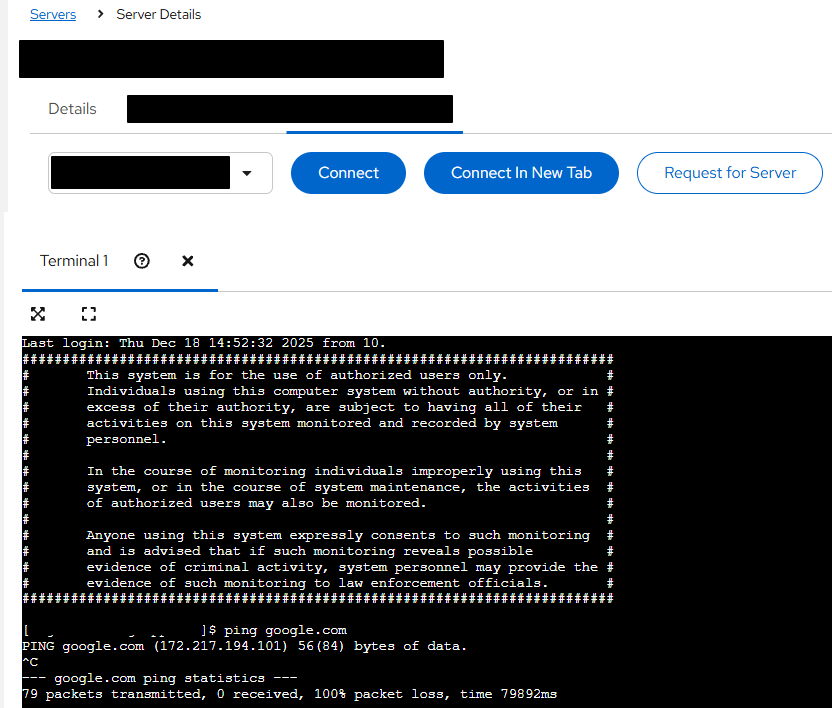

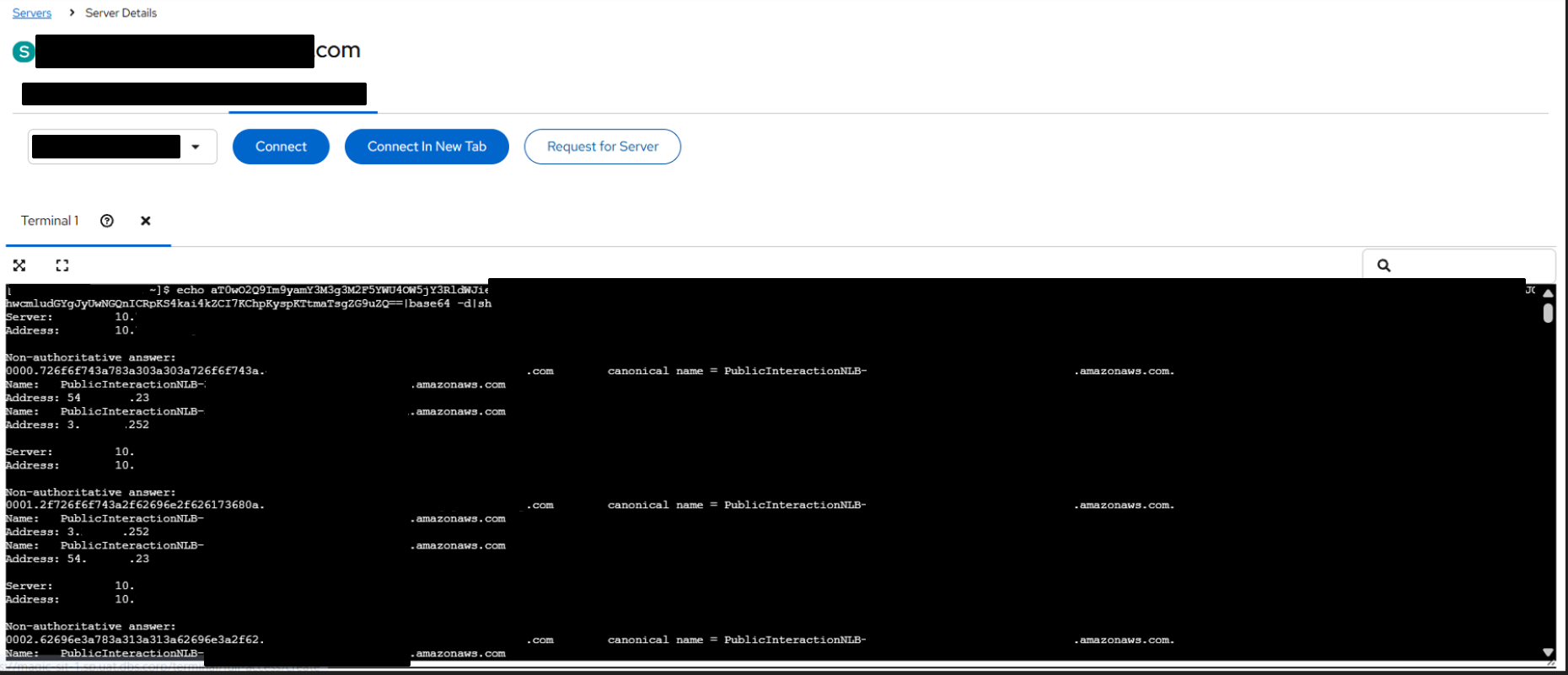

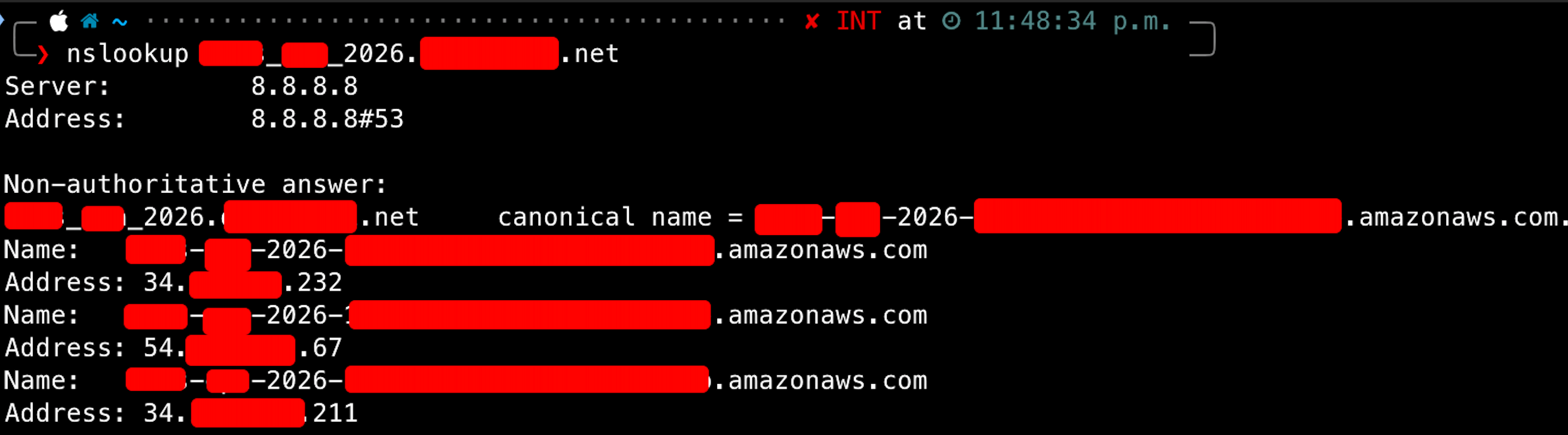

Step 1: Resolve the Original Domain to an IP Address

First, we need to determine the IP address associated with the original domain name. This can be done using the nslookup command:

nslookup <domain>

nslookup 2026_Test_jasveermaan.com

The figure below shows a successful nslookup result, returning the target IP address:

Make note of the IP address, as it will be required in the next step.

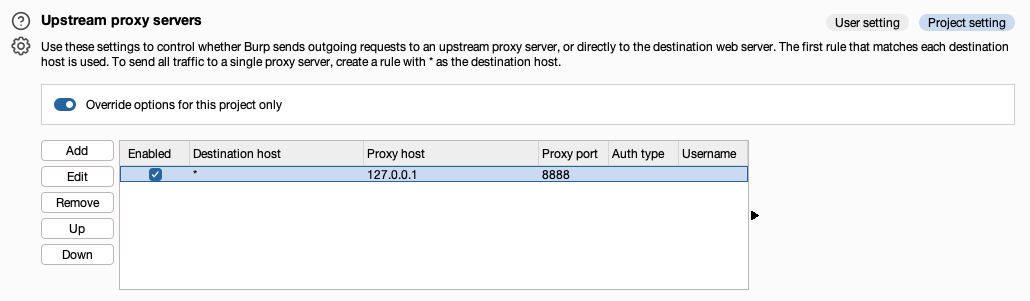

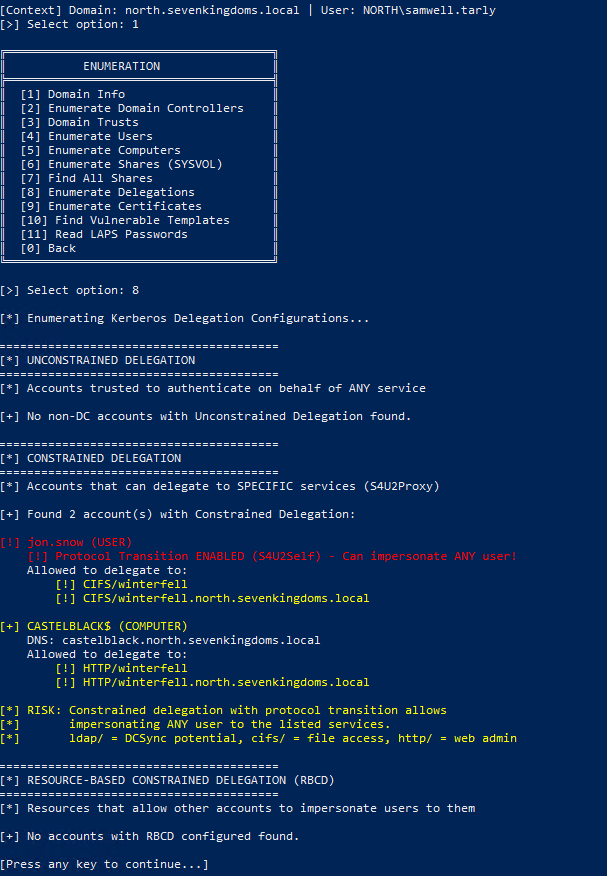

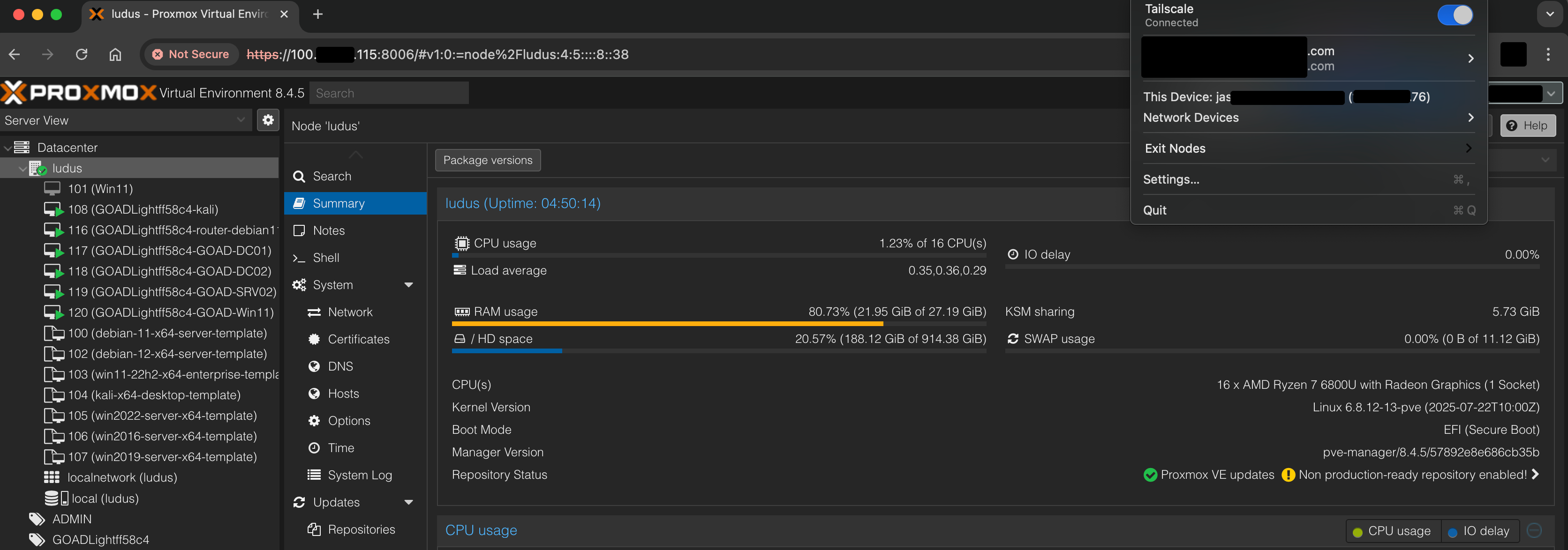

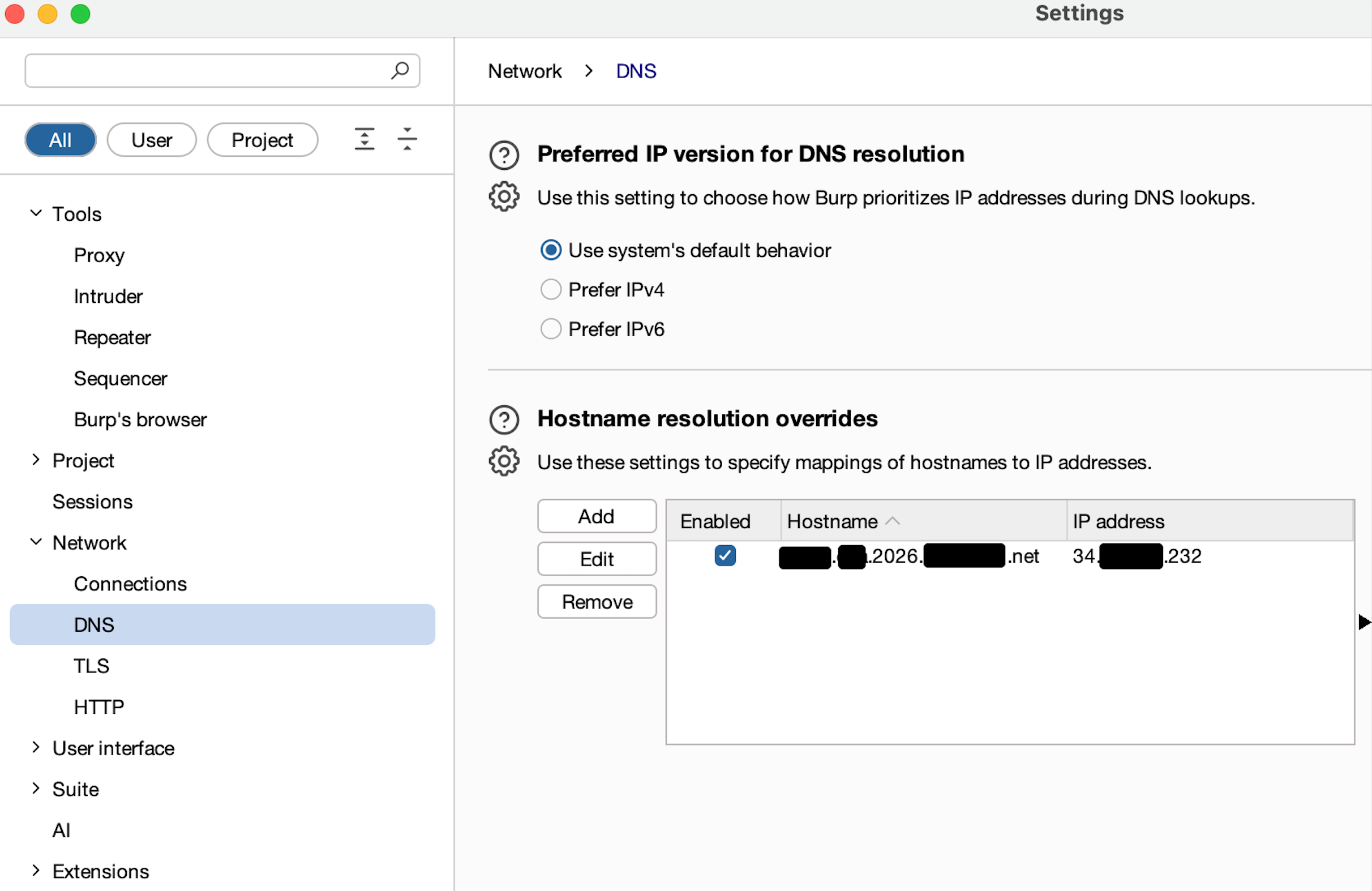

Step 2: Configure Burp Suite DNS Override

Since Burp Suite does not accept underscores in hostnames, we need to provide Burp with a modified version of the hostname that replaces underscores with dots.

Original domain:

2026_Test_jasveermaan.com

Modified domain:

2026.Test.jasveermaan.com

To implement this in Burp Suite:

- Go to Settings → Network → DNS

- Locate the section Hostname Resolution Overrides

- Add a new entry:

- Hostname: 2026.Test.jasveermaan.com

- IP Address: (IP from nslookup)

The figure below shows the DNS override configuration in Burp Suite:

At this stage, Burp Suite will resolve the modified hostname correctly.

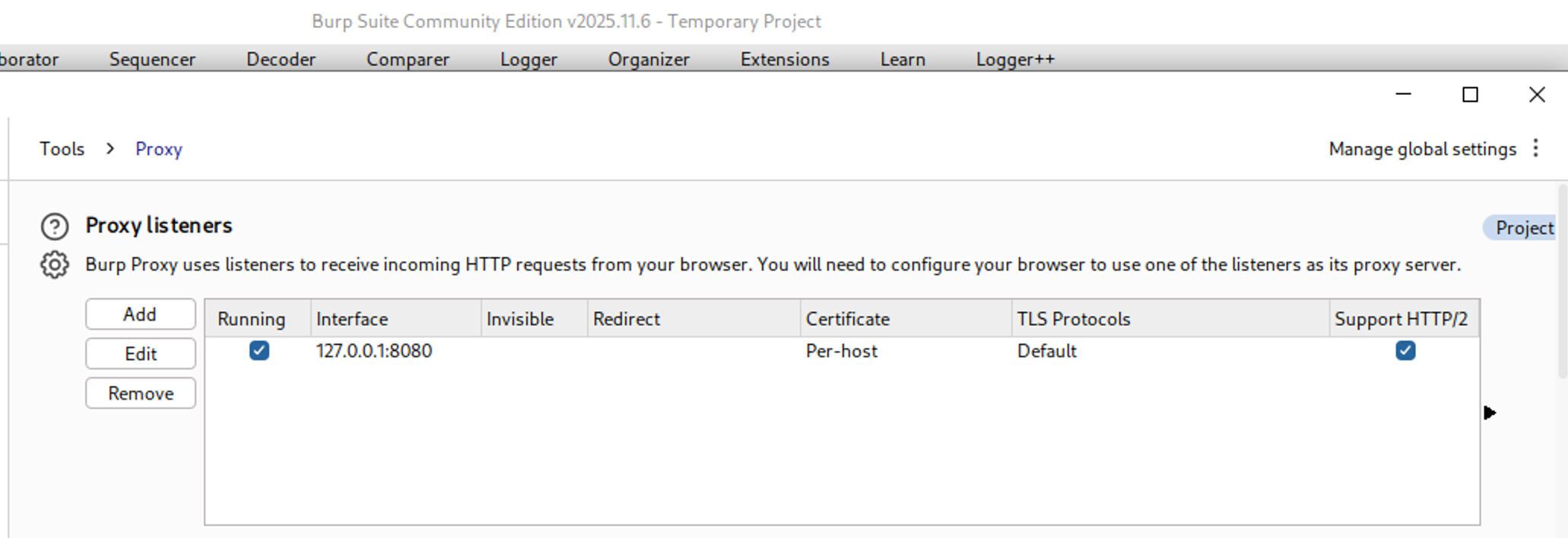

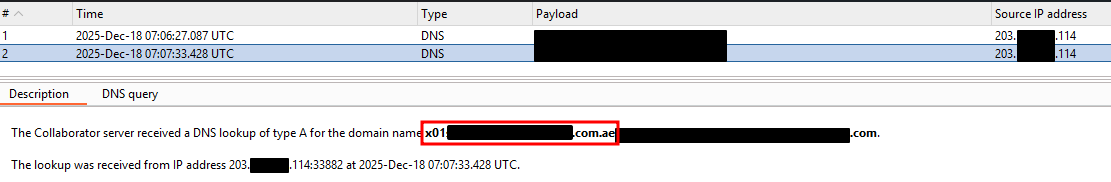

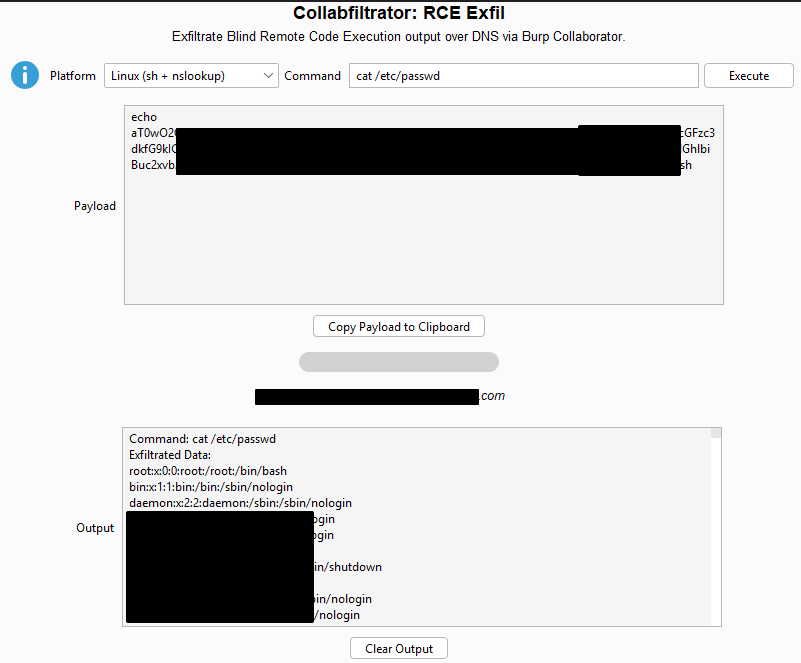

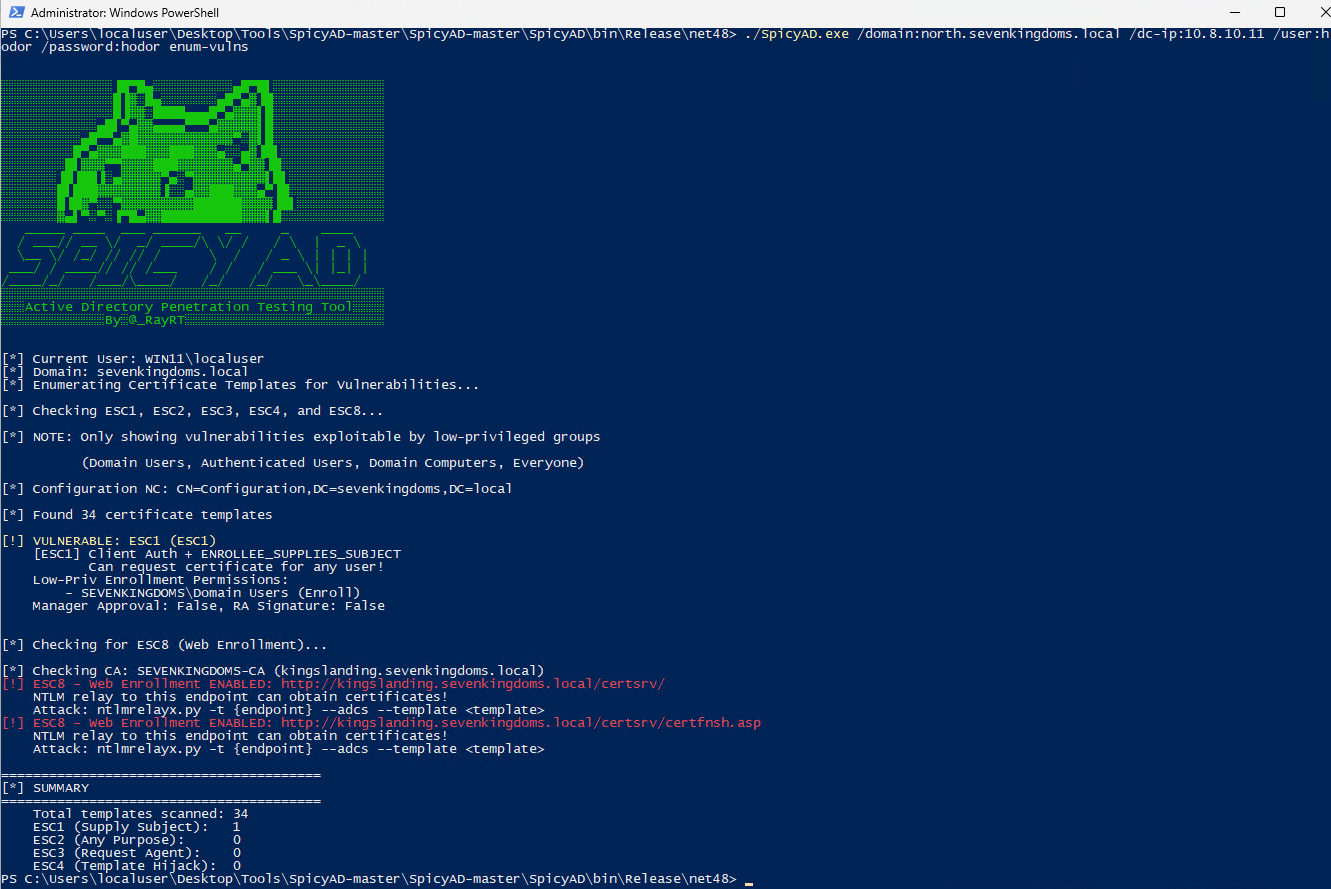

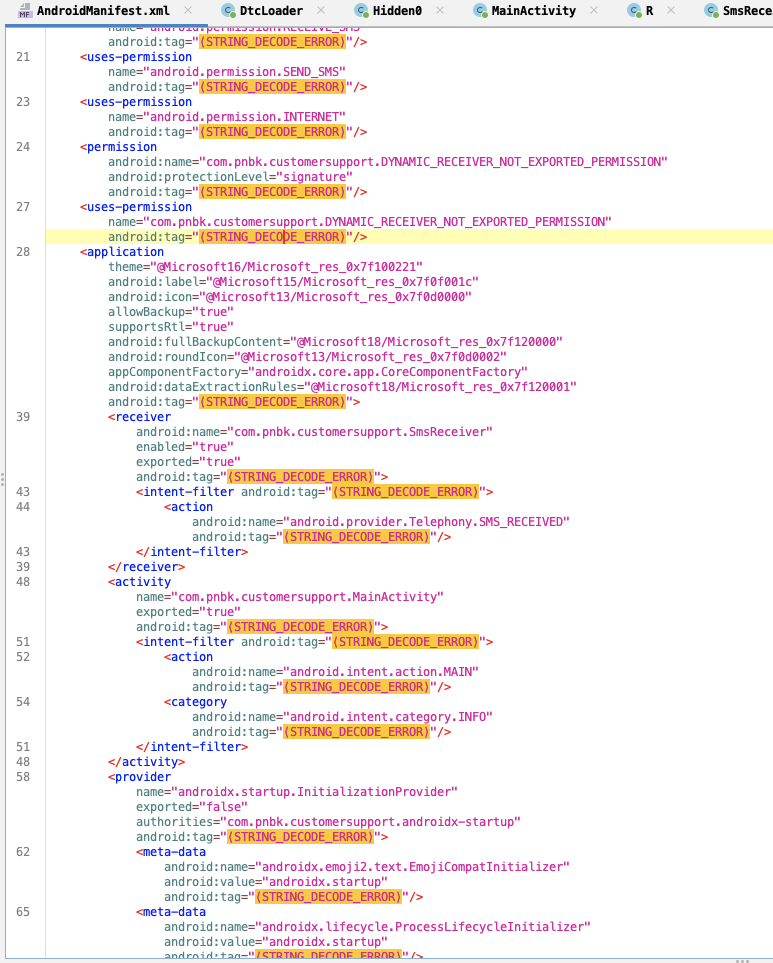

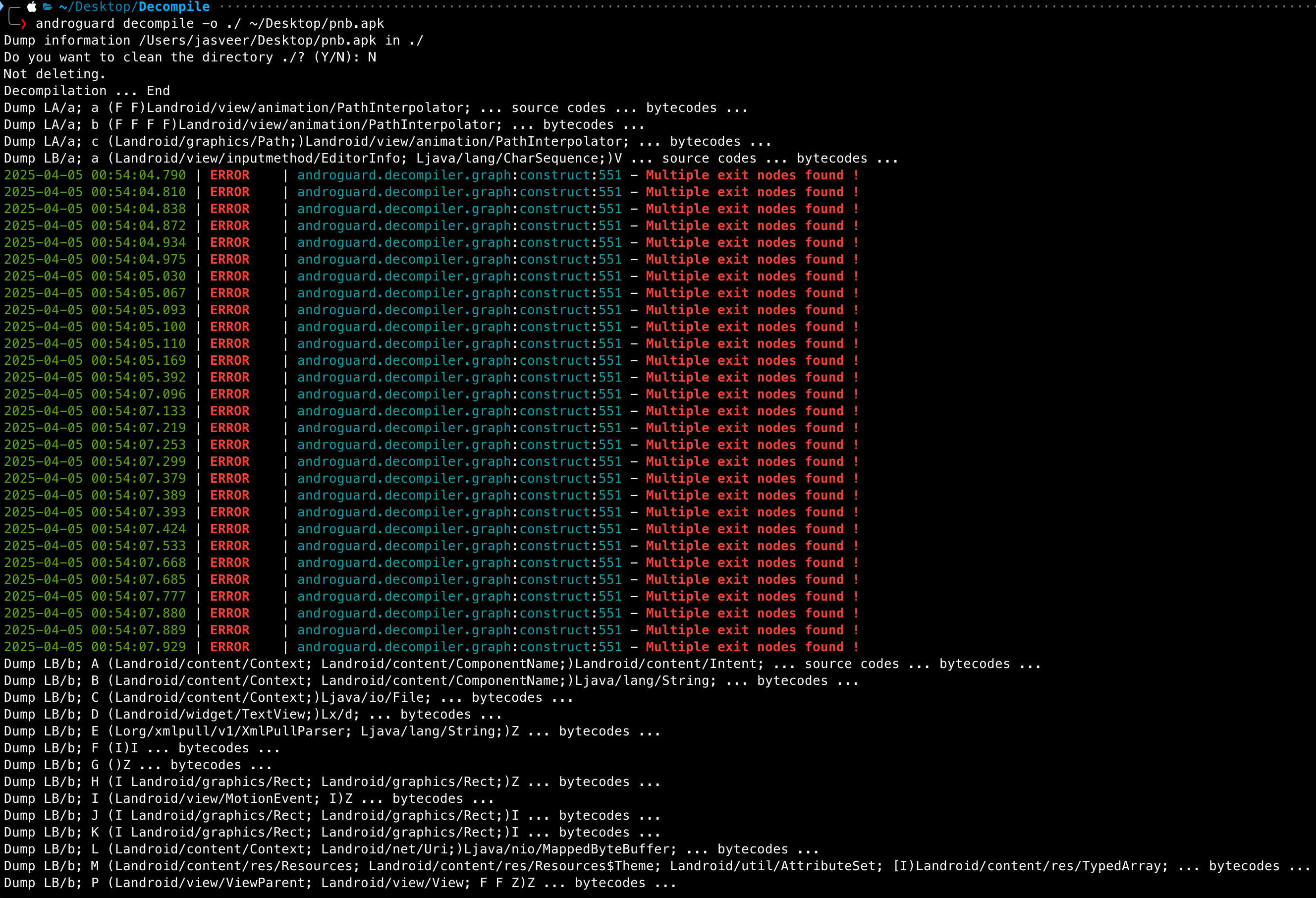

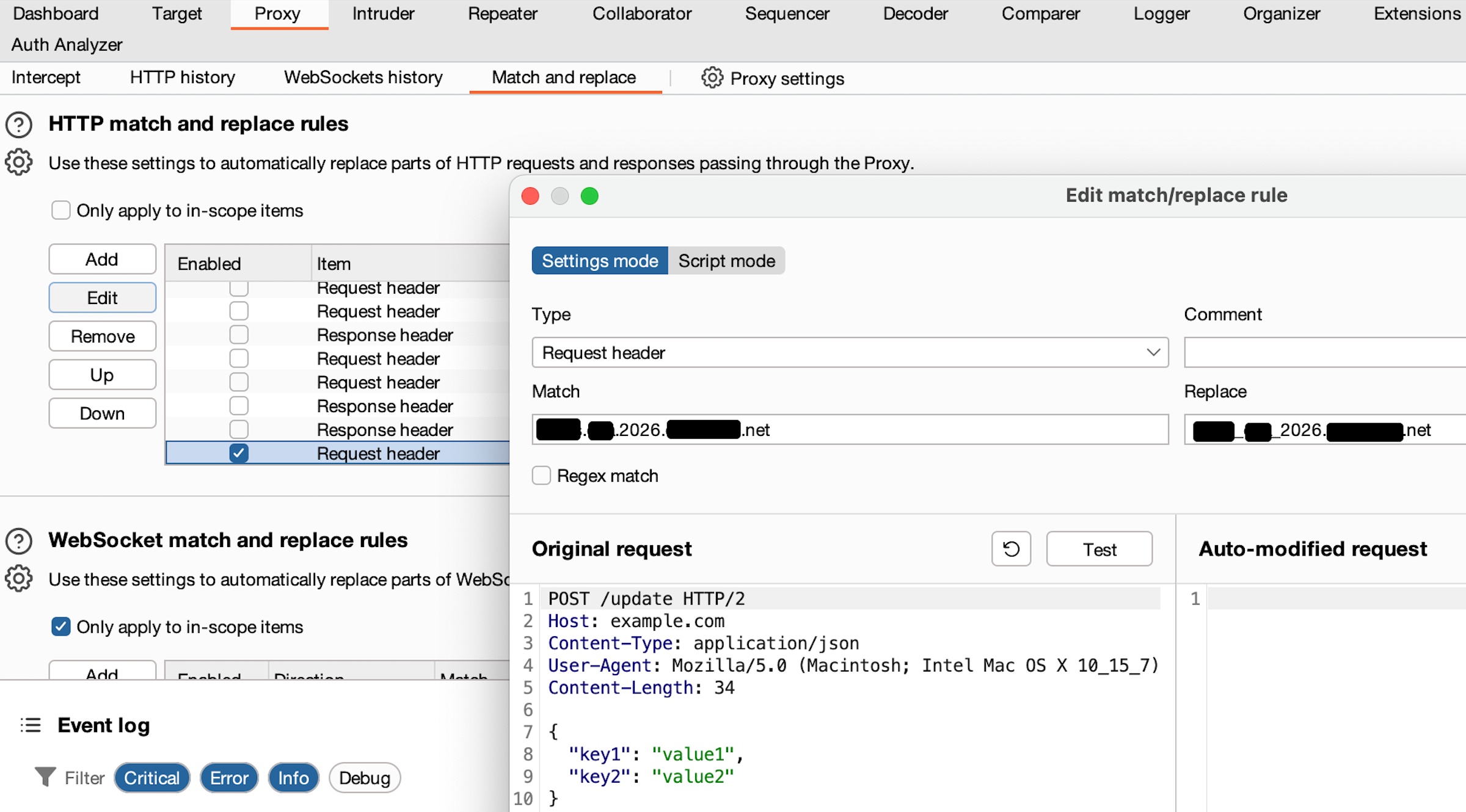

Step 3: Configure Match and Replace Rules

Although DNS resolution now works, the browser will still send HTTP requests using the modified dot-based hostname. However, the backend application expects the original underscore-based hostname in the HTTP Host header.

To resolve this, we configure Burp Suite to automatically rewrite the hostname before forwarding requests to the server. Navigate to:

- Settings → Proxy → Match and Replace

Create the following rule:

- Type: Request header

- Match: 2026.Test.jasveermaan.com (DNS Entry & URL that will be accessed via browser)

- Replace: 2026_Test_jasveermaan.com

This ensures that:

- The browser uses a valid hostname (with dots)

- Burp Suite can resolve the hostname correctly

- The request forwarded to the server still contains the original underscore-based hostname

The figure below shows the Match and Replace configuration:

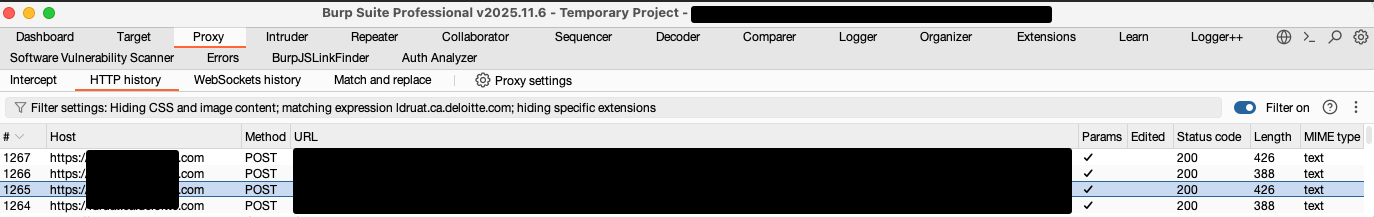

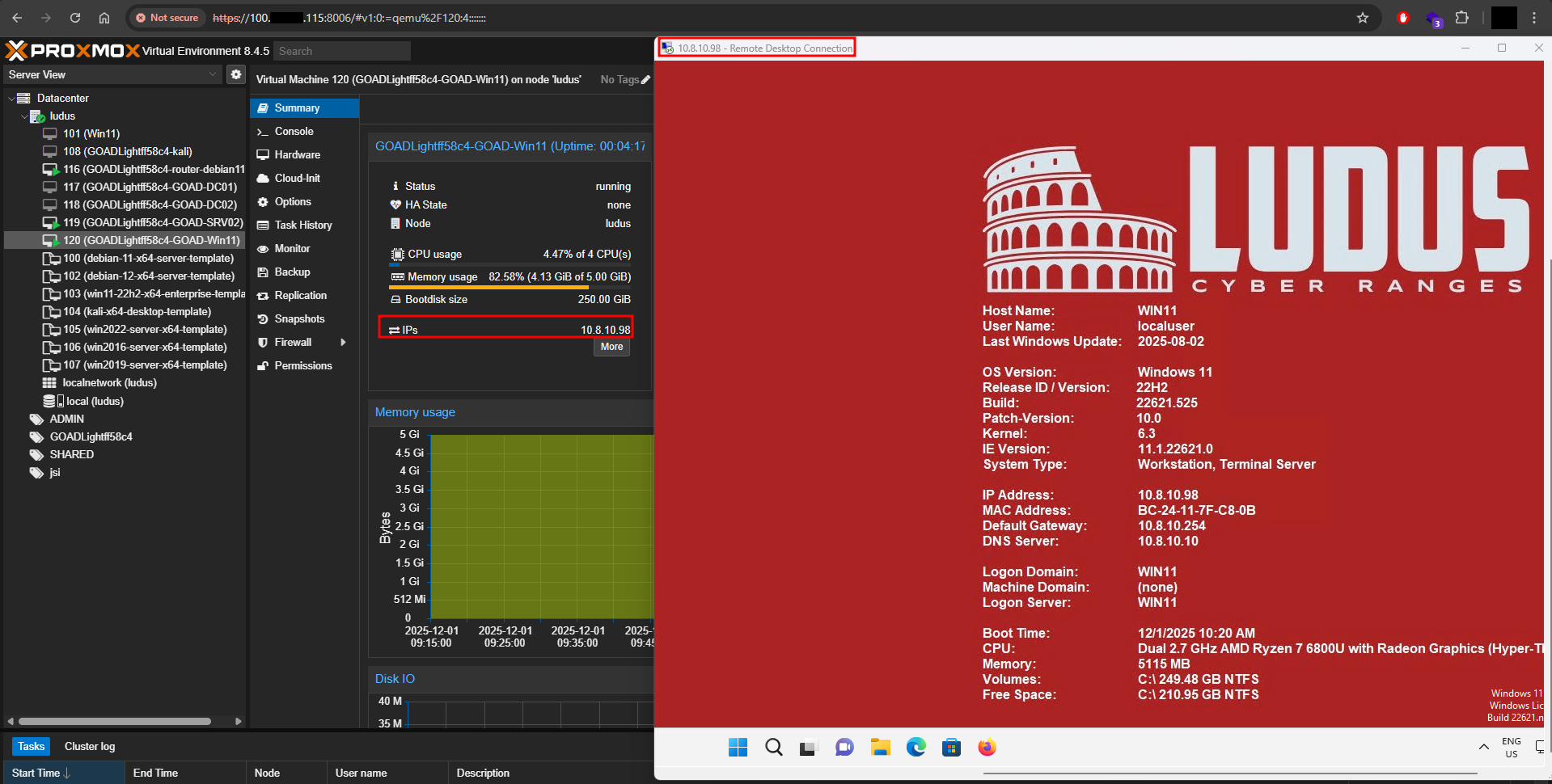

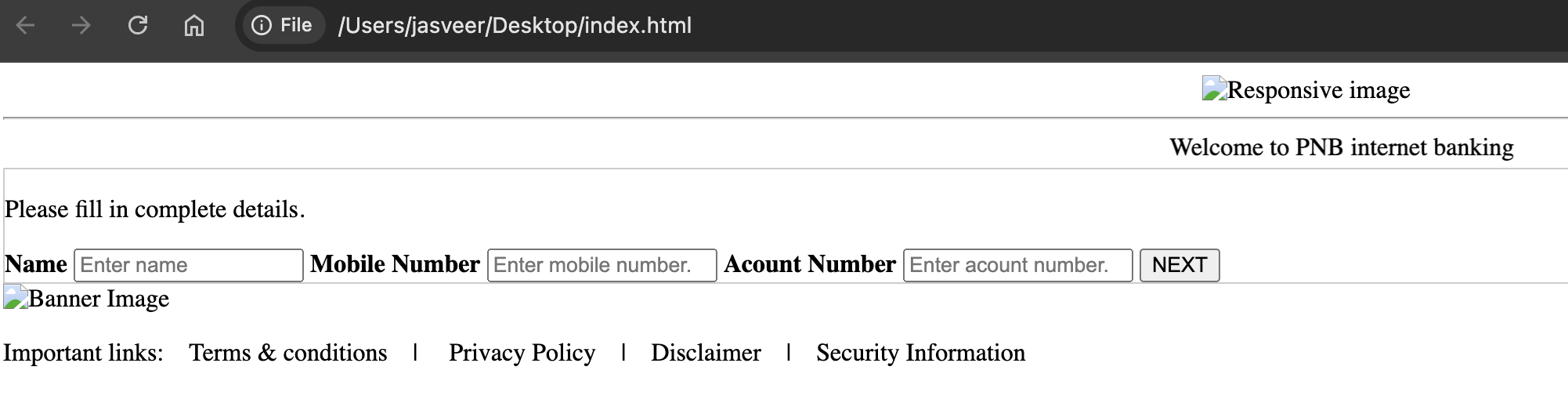

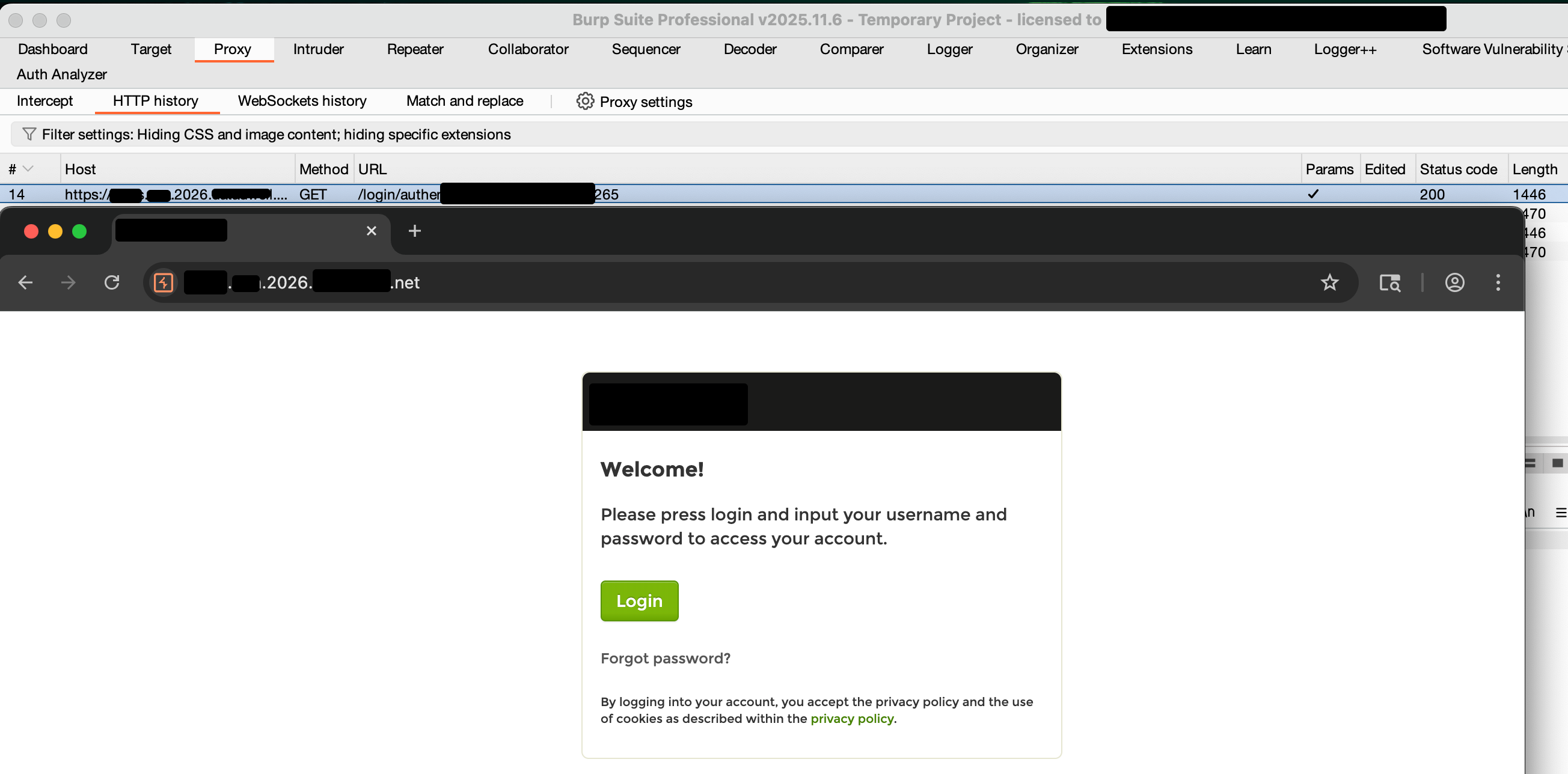

Final Result

After configuring both DNS overrides and Match and Replace rules, I launched the application again using Burp Suite’s built-in Chromium browser.

Instead of accessing:

2026_Test_jasveermaan.com

I accessed:

2026.Test.jasveermaan.com

Thanks to the configured rules, Burp Suite seamlessly:

- Resolved the modified hostname

- Rewrote the HTTP headers back to the original format

- Successfully proxied all client-server communication

The figure below shows Burp Suite successfully intercepting traffic without any errors:

Conclusion

This issue is relatively rare but can occur when testing legacy applications or environments where underscores are used in domain names.

While browsers may tolerate such domains, Burp Suite adheres strictly to hostname standards and rejects them.

By leveraging Burp Suite’s:

- DNS Hostname Resolution Overrides

- Match and Replace functionality

we can effectively bypass this limitation and continue testing without requiring any changes to the target application.

I hope this guide helps anyone who encounters a similar issue during a penetration test.